We at the SA just received the newest offering from the prolific Stephen Turnbull-“The Samurai Swordsman: Master of War”. As we speculated in a post a few months ago, the book is an expansion of his previous work, the long out-of-print “The Lone Samurai and the Martial Arts” (as he details in the introduction). You’ll also see it listed on different Amazon sites under its earlier proposed titles of “Art of the Samurai Swordsman” with Honda Tadakatsu on the cover, or just plain “Samurai”. It’s not an Osprey book (surprise!), but rather an impressive lengthy hardback (208 pages) published by Frontline Books (and in the US by Tuttle).

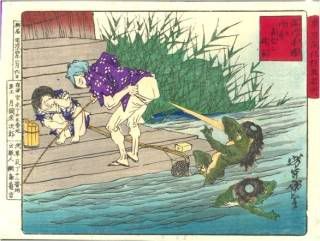

‘Samurai Swordsman’ is a coffee table book with an abundance of full color photos, prints, paintings, and portraits (some taking up two pages). Like most of Turnbull’s books, it’s a visual treat. It’s organized by chapter into several interesting themes and the incidents Turnbull lays out make for entertaining reading. There are basic chapters on general eras of Japanese history (ancient, Kamakura, Sengoku, Edo, and the Bakumatsu) along with several that focus on a specific subject (sword schools and styles, swords in society, vendettas and ronin, and female warriors). The evolution of the swordsman and the role of his weapon is traced throughout Japanese history from the early days of the Genpei war (when the bow was the weapon of choice for most samurai) through the Sengoku (where the spear and arquebus ruled the battlefield) into the Edo period, where the romanticized form of the samurai swordsman most westerners are familiar with (and that populate most chanbara films) began to take form. Notable early swordsmen such as Kamiizumi Ise-no-kami Nobutsuna geared their swordplay towards the practical, where it would be used under battlefield conditions. The (relatively) peaceful times under the Tokugawa Shogunate saw the highly stylized and regulated schools of swordplay take shape, resulting in a much more formal approach to swordplay more suited for individual duels. Also examined is how these more peaceful times gave rise to an idealized form of samurai behavior, bushido (which is espoused and followed much more ardently by self styled ‘modern sammyrai’ than it ever was by the real thing).

Turnbull also displays an excellent writing style, giving life and a dramatic flair to the tales of old. The careers of many prominent swordsmen are brought to life within its pages. From the usual suspects such as Miyamoto Musashi and the Yagyu to the more obscure (but perhaps superior) Chiba Shusaku and Takahashi Deishu, Turnbull gives both the historical reality and glorified legends that have sprung up around these figures. Turnbull’s strength lies in his descriptions and accounts of these old legends (along with the many illustrations and photos pertaining to these events, most from his personal archives), making his book an interesting contrast and companion to other recent works such as Thomas Conlan’s ‘Weapons & Fighting Techniques of the Samurai Warrior 1200-1877 AD’. Whereas Conlan meticulously deconstructs the traditional accounts (many of which are based on Edo period sources written decades after the fact) to show what is perhaps the kernel of truth that lies at their center, Turnbull gives the richness and impact of the stories that defined the glory days of the samurai. They’re interesting treatments of the same subject-the reality versus the ‘public face’ that helped shape the culture of Japan. In effect, they’re different facets of the same gem. Hence, we get the legends of female warrior Tomoe Gozen, the story of Akechi Mitsuhide’s mother being put to death in a botched hostage negotiation, and Asano Naganori (whose inept assault on Kira Yoshinaka in Edo Castle gave rise to the 47 Ronin incident) being called an ‘upstanding’ ‘well respected and experienced samurai’-all of which recent evidence suggests are false, but that have become widely accepted as fact both in Japan and the west.

The book does have a few editing problems (as virtually all texts dealing with history do). There are a few mismatched dates, and some photos appear to be mislabeled (such as a print on pages 182-183 dealing with the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 that implies the infamous Shinsengumi were present-a rather difficult feat since they hadn’t been around for several years by then). Turnbull’s bibliography is outstanding (with both English and Japanese language sources from academia and general surveys), and will give readers several excellent avenues to pursue further study.

Following Turnbull’s career has been an interesting exercise. From his first book in the late 70’s (The Samurai: A Military History, still my favorite Turnbull effort) through his latest effort 30 years later, he has done more to make pre-modern Japanese history accessible to most westerners than any other author. He’s never been afraid to alter his viewpoints or opinions when new evidence is uncovered (as perhaps best shown in his changing evaluations of the battle of Kawanakajima over the years). As the internet and advanced telecommunications have made certain works much easier to gain access to, his sources have become more varied and of better quality. Turnbull’s research habits and sources have become more involved, detailed, and diversified as well. He has produced some truly excellent and original works the past few years (with ‘Kakure Kirishitan of Japan’ on top, along with ‘Samurai Invasion’ and other short works on east Asian piracy, Kawanakajima, the Osaka Campaigns, and Japanese fortifications). His newest, ‘Samurai Swordsman’, would make a great book to give someone as an introduction to pre-modern Japanese history. It’s available directly from Frontline here. Our friends in Europe can also find it at Amazon UK and in the US from Amazon.

‘Samurai Swordsman’ is a coffee table book with an abundance of full color photos, prints, paintings, and portraits (some taking up two pages). Like most of Turnbull’s books, it’s a visual treat. It’s organized by chapter into several interesting themes and the incidents Turnbull lays out make for entertaining reading. There are basic chapters on general eras of Japanese history (ancient, Kamakura, Sengoku, Edo, and the Bakumatsu) along with several that focus on a specific subject (sword schools and styles, swords in society, vendettas and ronin, and female warriors). The evolution of the swordsman and the role of his weapon is traced throughout Japanese history from the early days of the Genpei war (when the bow was the weapon of choice for most samurai) through the Sengoku (where the spear and arquebus ruled the battlefield) into the Edo period, where the romanticized form of the samurai swordsman most westerners are familiar with (and that populate most chanbara films) began to take form. Notable early swordsmen such as Kamiizumi Ise-no-kami Nobutsuna geared their swordplay towards the practical, where it would be used under battlefield conditions. The (relatively) peaceful times under the Tokugawa Shogunate saw the highly stylized and regulated schools of swordplay take shape, resulting in a much more formal approach to swordplay more suited for individual duels. Also examined is how these more peaceful times gave rise to an idealized form of samurai behavior, bushido (which is espoused and followed much more ardently by self styled ‘modern sammyrai’ than it ever was by the real thing).

Turnbull also displays an excellent writing style, giving life and a dramatic flair to the tales of old. The careers of many prominent swordsmen are brought to life within its pages. From the usual suspects such as Miyamoto Musashi and the Yagyu to the more obscure (but perhaps superior) Chiba Shusaku and Takahashi Deishu, Turnbull gives both the historical reality and glorified legends that have sprung up around these figures. Turnbull’s strength lies in his descriptions and accounts of these old legends (along with the many illustrations and photos pertaining to these events, most from his personal archives), making his book an interesting contrast and companion to other recent works such as Thomas Conlan’s ‘Weapons & Fighting Techniques of the Samurai Warrior 1200-1877 AD’. Whereas Conlan meticulously deconstructs the traditional accounts (many of which are based on Edo period sources written decades after the fact) to show what is perhaps the kernel of truth that lies at their center, Turnbull gives the richness and impact of the stories that defined the glory days of the samurai. They’re interesting treatments of the same subject-the reality versus the ‘public face’ that helped shape the culture of Japan. In effect, they’re different facets of the same gem. Hence, we get the legends of female warrior Tomoe Gozen, the story of Akechi Mitsuhide’s mother being put to death in a botched hostage negotiation, and Asano Naganori (whose inept assault on Kira Yoshinaka in Edo Castle gave rise to the 47 Ronin incident) being called an ‘upstanding’ ‘well respected and experienced samurai’-all of which recent evidence suggests are false, but that have become widely accepted as fact both in Japan and the west.

The book does have a few editing problems (as virtually all texts dealing with history do). There are a few mismatched dates, and some photos appear to be mislabeled (such as a print on pages 182-183 dealing with the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 that implies the infamous Shinsengumi were present-a rather difficult feat since they hadn’t been around for several years by then). Turnbull’s bibliography is outstanding (with both English and Japanese language sources from academia and general surveys), and will give readers several excellent avenues to pursue further study.

Following Turnbull’s career has been an interesting exercise. From his first book in the late 70’s (The Samurai: A Military History, still my favorite Turnbull effort) through his latest effort 30 years later, he has done more to make pre-modern Japanese history accessible to most westerners than any other author. He’s never been afraid to alter his viewpoints or opinions when new evidence is uncovered (as perhaps best shown in his changing evaluations of the battle of Kawanakajima over the years). As the internet and advanced telecommunications have made certain works much easier to gain access to, his sources have become more varied and of better quality. Turnbull’s research habits and sources have become more involved, detailed, and diversified as well. He has produced some truly excellent and original works the past few years (with ‘Kakure Kirishitan of Japan’ on top, along with ‘Samurai Invasion’ and other short works on east Asian piracy, Kawanakajima, the Osaka Campaigns, and Japanese fortifications). His newest, ‘Samurai Swordsman’, would make a great book to give someone as an introduction to pre-modern Japanese history. It’s available directly from Frontline here. Our friends in Europe can also find it at Amazon UK and in the US from Amazon.