In chanbara, bloodletting comes in many forms. There’s

the one on one duel between sword masters (perhaps best exemplified by the

infamous ‘blood geyser’ duel between Mifune Toshiro and Nakadai Tatsuya at the

end of “Sanjuro”). Then there’s the fight between a harried single swordsman

and a small host of enemies (the climactic battle in “Sword of Desperation”).

From there it’s a small step to a single combatant facing a horde of enemies (Ichikawa

Raizo in “The Betrayal” or Wakayama Tomisaburo in the “Lone Wolf” series). And

of course, combine the two and you get the sword master versus a horde of

enemies AND a sword master (our favorite being the rumble between “Azumi” and

Bijomaru). But until 1963, large groups of swordsmen battling each other were

relatively rare in Japanese Cinema (especially if you discount the glut of 47

Ronin films). Enter director Kudo Eiichi and his so-called “Samurai Revolution Trilogy”-“13

Assassins”, “The Great Killing”, and “Eleven Samurai”. These films brought

brutal, extended street fights between opposing mobs of katana-wielding combatants

to the screen in a style Japan had never seen before. Today we’ll be looking at two B/W classics-1963's “13 Assassins” and '64's “The Great Killing” (“Eleven Samurai” will be released by

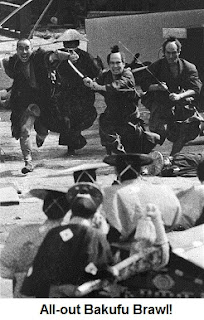

Animeigo in the near future). They’re all-out Bakufu brawlz that’ll leave you

feeling the need to mop invisible blood splatters off your face...

In chanbara, bloodletting comes in many forms. There’s

the one on one duel between sword masters (perhaps best exemplified by the

infamous ‘blood geyser’ duel between Mifune Toshiro and Nakadai Tatsuya at the

end of “Sanjuro”). Then there’s the fight between a harried single swordsman

and a small host of enemies (the climactic battle in “Sword of Desperation”).

From there it’s a small step to a single combatant facing a horde of enemies (Ichikawa

Raizo in “The Betrayal” or Wakayama Tomisaburo in the “Lone Wolf” series). And

of course, combine the two and you get the sword master versus a horde of

enemies AND a sword master (our favorite being the rumble between “Azumi” and

Bijomaru). But until 1963, large groups of swordsmen battling each other were

relatively rare in Japanese Cinema (especially if you discount the glut of 47

Ronin films). Enter director Kudo Eiichi and his so-called “Samurai Revolution Trilogy”-“13

Assassins”, “The Great Killing”, and “Eleven Samurai”. These films brought

brutal, extended street fights between opposing mobs of katana-wielding combatants

to the screen in a style Japan had never seen before. Today we’ll be looking at two B/W classics-1963's “13 Assassins” and '64's “The Great Killing” (“Eleven Samurai” will be released by

Animeigo in the near future). They’re all-out Bakufu brawlz that’ll leave you

feeling the need to mop invisible blood splatters off your face...Both of these films were based on actual historical incidents. “13 Assassins” abstracts the circumstances surrounding the death of Matsudaira Narikoto, the adopted son of Matsudaira Naritsugu (the daimyo of Akashi han in Harima province). Narikoto was considered to be bad news, at one point having apparently killed a small child for getting in his way. For this he was denied passage through Owari province, a major plot point in the film. He died of a ‘mysterious illness’ at age 20. “13 Assassins” changes Narikoto’s name to that of his adoptive father Naritsugu. In theory, this means the film takes place around 1844. “The Great Killing” is even more specific-it states up front it takes place in Enpo 6, or 1678. Here the character names and situations are taken straight from history-Sakai Tadakiyo did indeed attempt to keep Tokugawa Tsunayoshi from becoming Shogun, and Tokugawa Tsunashige did indeed die in 1678. Now, of course, you won’t find any records in the history books of these ‘mysterious deaths’ being the result of attacks by crazed bands of killers-you don’t think the Tokugawa would ever admit to that, do you? It never happened! Hey, it’s a plot device that worked out great for “Seppuku” (like “13 Assassins”, another film recently remade by Miike Takashi, this time using the “Hara-Kiri” title), so don’t knock it.

Screenwriter Ikegami Kaneo had already pioneered the “team versus team” style of Shudan Jidaigeki with “Seventeen Ninja” in 1963. The concept resonated with Japanese audiences who identified with the feeling of community between the protagonists more than they sometimes could with the headstrong individuals that were the heroes of other films. He joined forces with director Kudo Eiichi at Toei Studios to follow it up with “13 Assassins” (Ju-san Nin No Shikaku). With veteran screen legends Kataoka Chiezo (leader of the 13, Shimada Shinzaemon) and Arashi Kanjuro (his second in command, Kurenaga Saheita) anchoring the cast and newer actors like Tanba Tetsuro (Shogunate Elder Doi Toshitsura), strong individual performances were almost a given. Kudo decided he wanted the action to be more immersive than what was traditionally seen in most period films and shot many of the fight scenes using tracking shots with hand held cameras. While this is a common technique these days, one can only imagine the effect it had on Japanese audiences of the early 60’s who suddenly were put into the sandals of an attacker chasing his prey through a labyrinth of back alleys and dead ends. Being an experimental technique, things didn’t always go as planned. The cameras were huge and heavy, needing two men to carry them-and the viewfinders couldn’t be used, resulting in many shots being out of focus. While this infuriated Toei executives, it gave the shots that extra element of realism Kudo was striving for. It proved to be a hit with Japanese audiences-even today, Japanese cinema magazine Kinema Jyumpo considers “13 Assassins” to be the #2 Jidaigeki film of all time, trailing only Kurosawa Akira’s “Seven Samurai”.

“13 Assassins” is sometimes criticized as a knock-off of “Seven

Samurai”, and there are certain similarities. A team of skilled fighters is

slowly assembled to carry out a seemingly-impossible mission. One of the team seems

to be much more a farmer than a samurai, and another is the prototypical ‘inexperienced

kid’. Another is the master planner, with his loyal second-in-command, and a

badass sword master forms the fighting center of the group. A thoroughly

thought-out and executed plan leads to a final drawn-out battle that resolves

the fates of the combatants. However, at their core, they’re two different

types of films. “13 Assassins” essentially pits the samurai against their own

corruption and abuses. The ‘good’ samurai basically have to turn their backs on

the myth of Bushido to have a chance of success, and even if they pull it off,

there will be no acknowledgement or record of it. In effect, they’ve become stereotypical

ninja (hence the ‘Assassins’ of the title). The ‘bad’ samurai are in turn

defended by a mastermind who holds true to the precepts of loyalty to one’s

master and working within the guidelines of the Bakufu. Samurai leadership is

shown to be completely ineffectual in dealing with the crisis in an aboveboard

manner, but the evil lord Naritsugu’s twisted logic can defend his every

action.

“13 Assassins” is sometimes criticized as a knock-off of “Seven

Samurai”, and there are certain similarities. A team of skilled fighters is

slowly assembled to carry out a seemingly-impossible mission. One of the team seems

to be much more a farmer than a samurai, and another is the prototypical ‘inexperienced

kid’. Another is the master planner, with his loyal second-in-command, and a

badass sword master forms the fighting center of the group. A thoroughly

thought-out and executed plan leads to a final drawn-out battle that resolves

the fates of the combatants. However, at their core, they’re two different

types of films. “13 Assassins” essentially pits the samurai against their own

corruption and abuses. The ‘good’ samurai basically have to turn their backs on

the myth of Bushido to have a chance of success, and even if they pull it off,

there will be no acknowledgement or record of it. In effect, they’ve become stereotypical

ninja (hence the ‘Assassins’ of the title). The ‘bad’ samurai are in turn

defended by a mastermind who holds true to the precepts of loyalty to one’s

master and working within the guidelines of the Bakufu. Samurai leadership is

shown to be completely ineffectual in dealing with the crisis in an aboveboard

manner, but the evil lord Naritsugu’s twisted logic can defend his every

action. The film opens with the suicide of one of Lord Matsudaira

Naritsugu’s retainers. He sacrificed himself to bring the excesses of Naritsugu’s

behavior to the attention of the Shogunate’s Council of Elders. However, the

Council finds its hands tied-Naritsugu is the half-brother of the Shogun and in

line to become a highly placed councilor himself. Direct action against him is

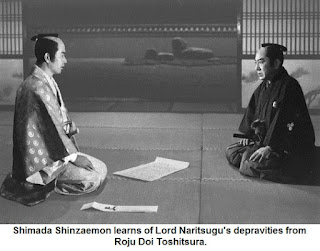

out of the question. Needing to employ more clandestine methods, Elder Doi

Toshitsura calls in Shimada Shinzaemon-one of the few men in an age of peace

who hasn’t neglected military strategy and training. After speaking to the

father of Naritsugu’s latest victims (the out-of-control daimyo raped a

retainer’s wife and then callously killed the retainer and the wife committed

suicide), Shimada agrees to ‘take care of the problem’. It’s decided to attack

Naritsugu’s procession as he returns to his fief-even then, he will have well

over a hundred retainers. Shimada is only able to cull 11 capable men from

among his numbers-his fallen nephew, seven police inspectors/retainers, and

three ronin. Realizing that proper planning will be essential for any chance of

success, they painstakingly put together a plan that they hope will split

Naritsugu’s forces and herd his reduced retinue into a specific town. With

ample financial backing from the Shogunate, Shimada’s group turns the town into

one giant death trap and hopes that the procession will find its way there.

Along the way they pick up their final member-a farmer claiming to be a samurai

who wants to join the fight to impress his girl’s father.

The film opens with the suicide of one of Lord Matsudaira

Naritsugu’s retainers. He sacrificed himself to bring the excesses of Naritsugu’s

behavior to the attention of the Shogunate’s Council of Elders. However, the

Council finds its hands tied-Naritsugu is the half-brother of the Shogun and in

line to become a highly placed councilor himself. Direct action against him is

out of the question. Needing to employ more clandestine methods, Elder Doi

Toshitsura calls in Shimada Shinzaemon-one of the few men in an age of peace

who hasn’t neglected military strategy and training. After speaking to the

father of Naritsugu’s latest victims (the out-of-control daimyo raped a

retainer’s wife and then callously killed the retainer and the wife committed

suicide), Shimada agrees to ‘take care of the problem’. It’s decided to attack

Naritsugu’s procession as he returns to his fief-even then, he will have well

over a hundred retainers. Shimada is only able to cull 11 capable men from

among his numbers-his fallen nephew, seven police inspectors/retainers, and

three ronin. Realizing that proper planning will be essential for any chance of

success, they painstakingly put together a plan that they hope will split

Naritsugu’s forces and herd his reduced retinue into a specific town. With

ample financial backing from the Shogunate, Shimada’s group turns the town into

one giant death trap and hopes that the procession will find its way there.

Along the way they pick up their final member-a farmer claiming to be a samurai

who wants to join the fight to impress his girl’s father.

Meanwhile, Naritsugu’s chief retainer Hanbei Onigashira

(who has deduced Shimada’s involvement) does his best to counter all of the

Assassin’s well laid plans. Despite having as much trouble dealing with

Naritsugu’s stubbornness as with Shimada’s measures, Hanbei manages to deftly

turn aside each challenge. It appears as if he’ll succeed in getting the

procession home safely…

The final battle, when it comes, is a long, brutal, and

lengthy affair in which every move made by the Matsudaira seems to have been

anticipated by Shimada. Traps and false escape routes sap the will of the larger

force. Mass slaughter ensues as Naritsugu’s forces scatter blindly in all

directions looking to escape the killing grounds. However, Hanbei proves up to

the challenge and despite huge losses manages to keep Naritsugu safe-with the

exit in sight. And don’t think you can guess the ending if you’ve seen the

remake.

The final battle, when it comes, is a long, brutal, and

lengthy affair in which every move made by the Matsudaira seems to have been

anticipated by Shimada. Traps and false escape routes sap the will of the larger

force. Mass slaughter ensues as Naritsugu’s forces scatter blindly in all

directions looking to escape the killing grounds. However, Hanbei proves up to

the challenge and despite huge losses manages to keep Naritsugu safe-with the

exit in sight. And don’t think you can guess the ending if you’ve seen the

remake. The movie is essentially split into two sections as far apart in tone as possible. Early on it’s all about setting things up-the plans, the personalities, the counter-measures, the preparations. It’s a traditional slow-moving, leisurely paced Japanese film. When it finally explodes into action, it turns the last third of the film into a non-stop battle with fighting that never lets up. Toei was generally known for having jidaigeki films that featured highly stylized kabuki-style swordplay, but that isn’t the case here-it’s down and dirty sword fighting with the participants becoming more exhausted the longer the fight goes on, their sanity leaving them as the horrors mount up. The sure strokes and proper form they exhibited earlier give way to feeble, spastic single-handed swipes at empty hair as they frantically try to stay alive.

“13 Assassins”, of course, was recently the subject of Miike

Takashi ‘s big budget 2010 remake. While we don’t really want to get into an

involved discussion of that film now, the two versions offer interesting

contrasts. Miike’s version starts off much like a shot-for-shot remake of the

original but soon shows its teeth with the graphic introduction of one of Lord

Naritsugu’s piteous victims. It introduces a bit more oddball humor (much of

which was cut for the American release), a lot more graphic violence and CG,

and surprisingly a bit more character development. Kudo’s original is far more

dark and serious with set pieces that don’t appear in the remake. The films

resolve differently as well, making them both well worth a viewing. In fact, it’s

one of those rare situations where a healthy debate can be justified over

whether the original or remake is a better film.

While “13 Assassins” is certainly deserving of its

reputation, Animeigo notes that “The Great Killing” (“Dai Satsujin”, The Great

Duel) is usually considered to be Kudo’s masterpiece. It has much in common

with “13”-a group of determined swordsmen sets out to kill a corrupt member of

the Tokugawa family despite overwhelming odds, culminating in a huge final

battle. However, this time, the Bakufu are the bad guys-Tairo (Senior Elder) Sakai

Tadakiyo is attempting to push his candidate for Shogun, Kofu Saisho (AKA

Tokugawa Tsunashige), into power through any means necessary. A cadre of the

Shogun’s personal guard opposes his plan and plots to destroy him-however, they

are betrayed, branded as rebels, and mercilessly hunted down by Sakai’s agents.

While “13 Assassins” is certainly deserving of its

reputation, Animeigo notes that “The Great Killing” (“Dai Satsujin”, The Great

Duel) is usually considered to be Kudo’s masterpiece. It has much in common

with “13”-a group of determined swordsmen sets out to kill a corrupt member of

the Tokugawa family despite overwhelming odds, culminating in a huge final

battle. However, this time, the Bakufu are the bad guys-Tairo (Senior Elder) Sakai

Tadakiyo is attempting to push his candidate for Shogun, Kofu Saisho (AKA

Tokugawa Tsunashige), into power through any means necessary. A cadre of the

Shogun’s personal guard opposes his plan and plots to destroy him-however, they

are betrayed, branded as rebels, and mercilessly hunted down by Sakai’s agents.

One of the rebels, Nakajima Geki, breaks into the home of

his friend Jimbo Heishiro (played by Satomi Kotaro, a link to the previous film

where he played Shinzaemon’s lackadaisical nephew Shinrokuro) looking for

sanctuary. It proves to be short lived. While Jimbo had no involvement with the

plot, he is lumped in with the rebels when Sakai’s men break into his home and

find Nakajima. They slay Jimbo’s new bride and what was an idyllic life turns

to hell within the space of a few seconds.

Jimbo manages to escape when his captors are set upon by

a rescue party, but the life he knew is now over. Resignedly, he joins the

group of conspirators in order to avenge his dead wife. They are few in number,

and in many cases only kept together by the rather hot body of Lady Miya. She’s

the niece of the group’s leader, Yamaga Soko, who is himself a student of Hojo

Ujinaga. And who’s Hojo? He’s Sakai’s Ometsuke (Chief Investigator) and has

been made responsible for ferreting out the rebels. This he does with relish in

some excruciatingly realistic torture scenes, including one where boiling water

is being ladled onto tied up victims.

Jimbo manages to escape when his captors are set upon by

a rescue party, but the life he knew is now over. Resignedly, he joins the

group of conspirators in order to avenge his dead wife. They are few in number,

and in many cases only kept together by the rather hot body of Lady Miya. She’s

the niece of the group’s leader, Yamaga Soko, who is himself a student of Hojo

Ujinaga. And who’s Hojo? He’s Sakai’s Ometsuke (Chief Investigator) and has

been made responsible for ferreting out the rebels. This he does with relish in

some excruciatingly realistic torture scenes, including one where boiling water

is being ladled onto tied up victims.

Yamaga gathers his ragged force and outlines his

plan-while they don’t have nearly enough force to successfully engage the

heavily guarded Sakai, they do have a chance of striking down Tsunashige.

Without Tsunashige, Sakai will no longer have a puppet to place in the

Shogunate-and his threat would be neutralized. It’s decided to divert and attack

Tsunashige’s procession as he returns to Edo after seeing Tokugawa Mitsukuni (yes,

Mito Komon hisself) back to Mito. Can a former Shogunate bodyguard, a wicked

priest, an umbrella maker, a ‘ninja girl’, and a handful of low-level officials

pull it off?

“The Great Killing” is a much more anarchic film than “13

Assassins”. While Sakai’s forces present a united front, the rebels are a

varied lot, from various backgrounds with different reasons for joining, many

of them of suspect loyalty. Some even prove to be worse criminals than their

enemies. Their plans are constantly changing as more members of the plot are

captured, and it’s sometimes hard to keep track of who’s fighting for whom. Unlike

“13 Assassins”, it’s tough to keep track of the sides during the final

battle-it just seems like a big frenzied free for all, but no less effective

for being so. The action moves from the streets of a crowded town into the

middle of a river, and since this is a Japanese film, there’s no guarantee of

anything resembling a happy ending-for either side. It also has an outstanding

delayed ending that we didn’t see coming until a few seconds before it

happened.

“The Great Killing” is a much more anarchic film than “13

Assassins”. While Sakai’s forces present a united front, the rebels are a

varied lot, from various backgrounds with different reasons for joining, many

of them of suspect loyalty. Some even prove to be worse criminals than their

enemies. Their plans are constantly changing as more members of the plot are

captured, and it’s sometimes hard to keep track of who’s fighting for whom. Unlike

“13 Assassins”, it’s tough to keep track of the sides during the final

battle-it just seems like a big frenzied free for all, but no less effective

for being so. The action moves from the streets of a crowded town into the

middle of a river, and since this is a Japanese film, there’s no guarantee of

anything resembling a happy ending-for either side. It also has an outstanding

delayed ending that we didn’t see coming until a few seconds before it

happened.

The camera work and shot composition is particularly

outstanding. There are bizarre, striking shots such as Sakai talking with one

of his underlings in an extended take-with the underling being “on screen” but completely

obscured behind a wall. This emphasizes the fact that while others might be

involved, it’s Sakai who is wielding all the power here-in effect, he’s the

only figure on the Bakufu side that matters. Another shot features rebels as

seen through cut-outs in a fence. This not only underlines the chaotic nature

of their mission but also the fractured state of their forces and the faint

hopes they have of success. There’s also a beautiful shot that involves an assassination

in a hall with backlit shoji screens.

Animeigo’s program notes also detail how Kudo used sound

in an innovative way. Wanting to use realistic crowd noises, Kudo taped audio

at several student demonstrations against the US/Japan alliance. He used the

resulting noise from the riots in the film, giving it a quite different vibe

than the usual canned crowd sound effects. If you listen closely during the

final battle, you can even hear police cars in the background! The “student

riot” angle becomes particularly intriguing when combined with the assassination

in 1960 of Japanese Socialist leader Inejiro Asanuma by a young right wing

student-an event captured on TV that might have contributed to the film’s

ending.

The transfers for both films are solid with Animeigo’s

typical superb translation and subtitling job. Both feature program notes that

give some of the historical background for their respective periods (both

scenarios are based on real-life events) as well as bios for the main actors

and crew. There’s the typical selection of trailers as well and small still

galleries as well. Interestingly, “Great Killing” lacks a title on the title

screen, something we also saw on Animeigo’s “Sword of Desperation”.

Taken individually or as a set, “13 Assassins” and “The

Great Killing” put you right into the action without incurring those annoying

sword wounds. They function both as traditional chanbara films and as straight

out actioners, groundbreaking films that set the stage for the increasingly

violent and more realistic efforts of the late 60’s and 70’s. And when you get

right down to it, who doesn’t want to take in two of the greatest on-screen

Bakufu Brawlz in J-Cinema? Seems that everyone likes seeing the Tokugawa have

it stuck to them.

“13 Assassins” and “The Great Killing” are available

directly from Animeigo at a discount, or through Amazon here and here.